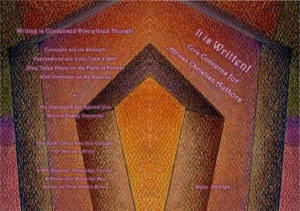

It is Written!

A Guide for African Christian Writers Steve Phillips

Steve Phillips

Writing is Condensed Disciplined Thought Concepts are its Strength Expressions are Your Team’s Skill Play Takes Place on the Field of Format With Grammar as the Referee ~ The Opponents Set Against You Are not Easily Overcome ~ This Book Cannot Give You Concepts Or Skill as a Writer ~ It Will, However, Encourage, Correct, & Advise You Along the Way Before the Final Whistle Blows

It is Written!

Core Concerns For African Christian Authors

Copyright 2019 by Steve Phillips

Cover artwork copyright 2019 by Patricia Phillips

All Rights Reserved

ISBN

978-978-56754-8-1

A composite English translation of the Bible

Has been used throughout

Behold Print Ventures

Plot 7, Elegbede Layout, Wofun Olodo Jenriyin,

Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria

+234 805 450 5578 +234 802 719 6424

bolarinwatt@yahoo.com

Table of Contents

Mandate to Write

Purpose

Benefits of Writing

Dangers of Not Writing

Tools

Interpretation

Observation

General Principles

Content

Intent

Confidence

Identity

Length

Style

Format

Procedure

Genre

Experiment

Appendix: Grammar & Punctuation

Grammar

Punctuation

It is Written!

A Guide For African Christian Writers

Mandate to Write

“Write this for a memorial in a book” –Ex.17:14.

“You shall write them on the doorposts of your house and on your gates” –Deut.6:9.

“Write it on a tablet before them and note it on a scroll that it may be in the time to come as a witness forever” –Isa.30:8.

“Write for yourself all the words which I have spoken to you in a book” –Jer.30:2.

“Write it [the whole “design of the house”] in their sight so that they may keep its whole design and all its statutes and do them” –Ezek.43:11.

“Write the vision and inscribe it on tablets that he may run who reads it” –Hab.2:2.

“What you see, write in a book and send it to the seven churches” –Rev.1:11.

Purpose

Christian writing is not to inform but to transform

Clarity: “We are writing nothing else to you than what you read and understand” -2 Cor.1:13.

Exhort: “I am writing unto you in which I am stirring up your pure minds by way of reminder” -2 Pet.3:1.

Preventative: “To write the same things again is no trouble to me, but for you it is safe” –Phil.3:1.

Preventative: “These things I have written to you concerning those who are trying to deceive you” -1 Jn.2:26.

Warning: “I found it necessary to write to you exhorting you to contend earnestly for the faith” –Jude 4.

Obedience: “I write so that you will know how one ought to conduct himself in the house of God” –I Tim.3:15.

Obedience: “For to this end I write, so that I might put you to the test, whether you are obedient in all things” -2 Cor.2:9.

Fellowship: “That which we have seen and heard we declare to you, that you also may have fellowship with us. These things we write unto you that your joy may be full” -1 Jn.1:3,4.

Explanation: “All this, the Lord made me understand in writing, by His hand upon me, all the works of this pattern” -1 Chron.28:19.

Encouragement: “He sent letters to all the Jews…words of peace and truth” –Esth.9:30.

Memorial: “Then those who feared the Lord spoke to one another and the Lord gave attention and heard them, and a book of remembrance was written before Him for those who fear the Lord and who meditate on His name” –Mal.3:16.

Worship: “My heart overflows with a good theme; I am saying my works to the King; My tongue is the pen of a ready writer. You are fairer than the sons of men” –Ps.45:1,2.

Durability: “Oh that my words were written! Oh that they were inscribed in a book! That with an iron pen and lead they were engraved in the rock forever!” –Job 19:24,25.

Benefits of Writing

Reformation cannot exist, much less thrive, in ignorance. The dismal bondage of humanity’s mind during the Dark Ages must come to an end. The Lord wants the common man to know the truth that he might be set free.

And so it was that a wonderful invention was perfected that forever after completely transformed the lives of men and the history of the world. In 1456 Gutenberg had completed the first printing press with movable type. His initial production was two hundred copies of the Word of God printed in Latin.

By 1483, numerous printing presses throughout Europe were producing many different books in a wide range of languages. Printing and literature in the hands of the literate cannot be underestimated in the progress of reformation.

God is literate. He not only speaks, He writes.

Paul commands that his letters be read to all the brethren [I Thess.5:27; Col.4:16]. Common men are commanded to read and reason from the written Word of God for themselves. “Search from the Book of the Lord and read!” -Isa.34:16. Even children are to gain their doctrine from the Scriptures directly [2 Tim.3:15].

When asked, “What must I do to inherit eternal life?” Jesus replied: “What is written in the Law? How does it read to you?” – Lk.10:25,26. A thrice repeated, “It is written” – Mt.4:4,6,10 effectively silenced the oral assaults of the devil.

Writing transports a reader beyond the narrow confines of his immediate experience and the smallness of his own thoughts. Thereby he is carried into vast vistas of unexplored regions. As well, the author himself travels far beyond his own tiny environment and visits heretofore unknown people through the distributed printed page.

By writing, a living reflection is captured in words and imprisoned on the page. Secured in durable form, it continues to live therein. By having done so, other reflective minds can partake of living thoughts as they interact with the written page.

Thus the printed page provides an unchanging reference point for repeated reflection. Thereby waywardness can be arrested by bringing original declarations into present circumstances. “Now go, write it on a tablet before them and inscribe it on a scroll that it may serve in the time to come as an everlasting witness” -Isa.30:8.

Thereby the thoughts and convictions contained in quality writing can span generations. And even after the author has died, like Abel, he still speaks for his God [Heb.11:4].

Writing cancels the bondage of hierarchy stemming from oral tradition. By it each must judge for himself the message received. Writing provides an external referent independent of the one speaking it. And that of the Scriptures thereby judges all men [Acts 17:11; 1 Cor.10:15; 1 Cor.14:29].

Though Revelation and Inspiration ceased with the Apostles, understanding and apprehension continues and develops. We can expound upon but not add to the Revelation of God’s Word. But we need not be able to read the Scriptures in their original Hebrew and Greek languages to do so.

The truth of the Scriptures can be expressed in writing in other languages outside those of the original written revelation. This is shown by the NT’s use of the Septuagint [LXX], the Greek translation of the OT [c. 225 BC], which preserved its truth in the same common language of the people of the first century.

And thus by the NT’s use of the LXX, the Bible itself prepared the way for its translation into the languages of all peoples. Gutenberg and those after him were granted wisdom and skill to print the Word in durable quantities so that its blessed light might radiate into the hearts of the world’s millions.

Dangers of Not Writing

Writing preserves the objective content of Christianity

Beyond the writer’s generation

Functionally illiterate: we meet it constantly. Students “read” the Scriptures out loud and are somehow barely able to phonetically pronounce the words; but there is very little comprehension of what they have mouthed. Analytical critical thinking skills are a rarity. The very idea of deriving truth for themselves from what they have gleaned as they read is a culturally foreign idea to them.

Centuries of bred-into-the-bone rote memory and repetition of what they have orally received by tradition is a paradigm more daunting than the 60-foot-thick walls of Jericho. The entire traditional African culture mitigates against development of independent assessment and drawing of conclusions other than what they have always known and been told.

Our task is not merely to proclaim a true message; that must be done. But there is also an entire re-orientation of how truth is derived if our Christianity will endure beyond our lifespan. It is a cultural revolution that writing in and of itself confronts.

The progress of genuine Christianity must be prosecuted on two levels if it will be sustainable into succeeding generations; [1] we must present the true written content of the Scriptures and [2], address the very mental mechanism by which it is apprehended. Without the latter, our content will soon be overtaken by the weeds of oral tradition and no fruit brought to maturity.

Oral tradition [Orality] fosters and creates hierarchy. Writing places every individual on an equal plane. Orality keeps subordinates dependent. Writing liberates the individual from those shackles. “Truth” in traditional societies is the privileged portion of the elite. Truth via writing exposes its message to all irrespective of status or station.

And it is here that a great cultural upheaval must take place for the truth of the Written Word of God to take deep root and spread throughout the land. It is not merely that the new content of the gospel must be received. If it is received within the traditional paradigm of orality, then the default mindset will twist even that message to conform to its presuppositions and world-view.

And it takes years of repetitively requiring people to reason for themselves via inductive questioning that a new mind-set emerges. And there are no shortcuts that are apparent to hasten this development.

By engaging men thus, the individual is ennobled as a dignified person equally created in the image of God. By doing so, it gradually will dawn upon him that he has something worthwhile to contribute, that his thoughts and reflections have value.

He will realize that not only is he no more in bondage to others’ unquestioned directives, but that he also has a voice with something significant to say. By developing his reasoning process through repeated solicited responses to inquiries, he learns to analyze on his own. Confidence is thereby instilled that he is capable, not only of receiving new ideas from the Word, but also of discovering them for himself by the illumination of the Spirit.

Thus by stimulating, activating, and training his own inherent reflective skills, he is weaned from dependence upon man and gains trust in the Holy Spirit’s instruction to his heart apart from human mediators. He will know the truth, not only that of new content, but the truth of the Spirit’s enablement of his enlightened mind. And those twin truths will set him free indeed.

And if this is not forthcoming, our Christianity will remain held captive by the new oral tradition of the “Man of God,” the Ifa of the sanctuary. That is our daunting task and the gravity of whether or not Nigeria will emerge as the next global torch bearer as the sun sets on the Western world.

It is not by coincidence that Gutenberg’s press was perfected only some few short years prior to the Reformation in Europe. Literature fuels reformation. Apart from that, either the bondage of Orality remains in force, or the onslaught of the visual media of Digitality will overwhelm.

Biblical truth, in WRITING, cancels hierarchy, ennobles the individual, liberates the mind, enhances reasoning, and transports beyond the narrow canyon walls of one’s own cultural experience.

The Scriptures supplant oral tradition. That Word is external, objective, and verifiable. It is preserved in durable form available for all to read and judge whatever anyone says concerning it.

Oral tradition follows the crooked trail through the bush over centuries of time. Each individual is expected to walk in the same path established by the ancestors without questioning. Because it is passed on orally, manipulation and misrepresentation are easily achieved in the mouth of the one in authority who speaks it.

Orality is purely subjective. Its message is completely dependent upon the one speaking. The speaker can invent whatever he wishes to influence and control others; and the hearers have no way of knowing whether he has done that or not. This is what is meant by subjective; nothing outside the man’s own report exists to verify his statements.

Writing, however, places every man on the same level. Each must interact with the message and decide for himself. The Word judges every man, both elder and youth alike. And at the same time, the reader is judging what he reads in order to understand its content.

And thus by the very fact of having a written Word, the evil of ruling over others in the church is cancelled. The oppression of clergy dominating the laity [common people] has no place when there is a written Word available to all: “I speak as to wise men; you judge what I say” -I Cor.10:15.

Orality also reinforces tribalism. Only the message of one’s particular tribe handed down by the elders has validity in African Traditional Religion [ATR]. Other traditions and customs are therefore looked down upon as inferior, weak, and irrelevant.

The written Word, however, eliminates all basis for tribal superiority. All are equal members of a new family, a new community, a fellowship that does not take into account any man according to what he is in the flesh. “Therefore from now on we regard no one according to the flesh…he is a new creation; the old things have passed away” -2 Cor.5:16,17. “All of you…have clothed yourselves with Christ. There is neither Jew nor Greek…slave nor free…male nor female” -Gal.3:27,28.

Oral tradition keeps one a prisoner of his own isolated world. He knows nothing outside of what he has been told to believe. Other perspectives are suspect and resisted. What others think and practice is rejected as alien, inferior, and threatening.

But with writing, one is transported beyond the limits of his own immediate experience. Vast new vistas of knowledge are opened up to the mind to consider. And the Scriptures go even further; they carry us beyond everything known here below on earth to now view life from a higher, heavenly, and eternal standpoint.

“As it is written, ‘Things which eye has not seen and ear has not heard, and which have not entered the heart of man’…to us God revealed them through His Spirit…not in words taught by human wisdom, but in those taught by the Holy Spirit, combining spiritual thoughts with spiritual words” -I Cor.2:9,10,13. We must repent of the twisted deceptive path of oral tradition.

Quite in contrast to Orality, writing and the Word of God are objective. They are not dependent upon the man who is speaking about them. They are outside the man, can be read by all, and each person can judge for himself whether what the man is saying is what is actually written.

There are three global paradigms affecting every person:

Orality, Writing, and Digitality. Orality is the oldest of the three historically. The other two have emerged later as cultural revolutions.

In Orality, the ear is the gate to dominating subordinates. In Writing, the mind is the gate to liberating individuals. In Digitality, the eye is the gate to manipulating the masses.

In Orality, the entire traditional culture mitigates against development of personal opinion and inventiveness. Independent reflection and assessment is discouraged and even forbidden. Ancestral tradition handed down via the elders must prevail. Any deviation is punishable.

Writing is a cultural revolution in and of itself. With Writing, there is an entire re-orientation of how truth is derived and understood. Writing presents an external, objective, and verifiable referent for ideas and truth. Each person must interact with concepts for himself, regardless of what others may think or say.

But we are faced with yet another powerful threat to the extinction of the objective content of Christianity. The global storm looming on the horizon is the paradigm shift of Digitality.

Images signal the demise of writing. All is processed via edited icons of pixelated portrayal [Pixels: tiny areas of light on a display screen which make up an image]. Reality is not actually viewed, but a carefully selected visual stimulus is presented as true.

Digitality results in the resignation of reflective rational properties that are replaced by sensual impressions absorbed via edited images. Images are not the essential and substantial form of things, but only project a representation and manifestation of the editor’s message.

This visual medium signals the onslaught of a highly manipulative communication means that is processed subjectively by the viewer. The stream of these impressions is emotionally judged by the sensual effect they have upon the individual. Feelings thus influenced incline the observer towards the direction of the digital composer.

32 frames per second in video production present the illusion of movement. The viewer is unaware of fixating upon a sequence of recorded pictures rapidly passing before his eye. The bombardment of stimulus at such a rate is accepted as reality without engaging reflective mental analysis. The relentless digital flow of images precludes studied contemplation by the speed that successive pixels assault the eye, leaving their subjective impressions as they swiftly pass.

In both Orality and Digitality, the individual is a receptor, but is not engaged as an active participant. In neither are the agreement nor contribution of the individual expected or solicited.

Writing anticipates and requires interaction, assessment, and invites the participation and consideration of the reader. Writing not only permits, but demands critical judgment of its content.

Orality and Digitality proceed with their fables and films without allowing the hearers and viewers opportunity to reflect, analyze, and conclude. They are fluid mediums and stream without interruption.

Writing is static, accommodates the pace and capacity of the reader, and welcomes periods of unhurried reflection before resuming the writer/reader dialogue. Orality and Digitality both are monologues of motion that invite no interruptions.

Only in writing is the individual a participant. Writing asks the question: “What do you think?” Orality and Digitality pose no such query. They simply pontificate with their predetermined and expected outcomes resulting from hearing and seeing their respective diatribes.

Witness in Mt.4 how each cultural paradigm is employed by the devil against the Lord Jesus. He first assaults Christ on the basis of Orality: “Command these stones to become bread.” Appeal is made to the authority of Oral Tradition in the mouth of the speaker, in this case, that of Satan himself.

The devil also is adept at employing Writing in attempts to lure astray not only Christ, but the godly as well: “Cast Yourself down, for it is written.” Here the content he quoted from Ps.91:11,12 was correct, but the reasoning process used to assess the Word was not. And thus unless both content and its assimilating procedure utilized to gain understanding and to interpret truth is transformed, content will revert to its default of Orality; it will mean only what the speaker says it means.

Finally, the tempter employed Digitality to impress and overwhelm; he showed Christ “all the kingdoms of world and their glory in a moment of time.” Imagine the sensual bombardment of this, leaving one nearly stunned by the rapidly flashing images passing before one’s awareness. It may prove at last to be the most threatening and effective medium of mass manipulation.

Christ counters all three paradigms of temptation by a single recourse: “It is Written.” The unchanging Word of God in its durable written form is the only effective means of escaping the tempter’s snares of both Orality and Digitality.

In both Orality and in Digitality, the direction of the life are governed by internal, subjective, and non-verifiable sources: either submitting to Traditional perspectives via Orality or to Sensual Impressions by means of Digitality.

The Written Word of God safeguards against both. It is external, objective, and verifiable. It is not dependent upon verbal report from an elite eldership as in Oral Tradition. Neither are the Scriptures to be received and followed based upon emotional sensations absorbed through Digitality’s sensual impressions.

IT IS WRITTEN cancels the bondage of Orality. IT IS WRITTEN subverts the sensual impressions of Digitality. IT IS WRITTEN establishes the truth of the Word of God interpreted in context, illumined by the Spirit, proclaimed fearlessly, and upheld without compromise.

IT IS WRITTEN: “Forever, O Lord, Your Word is settled in heaven” -Ps.119:89.

IT IS WRITTEN: “I esteem right all Your precepts concerning everything; I hate every false way” – Ps.119:128.

IT IS WRITTEN: “The Lord brings the counsel of the nations to nothing; the counsel of the Lord abides forever!” -Ps.33:10,11.

IT IS WRITTEN!

Tools

King James Version: [KJV] is a must. It has been the standard translation of the Bible for more than four hundred years. It cannot be ignored if you wish to understand how Christian thought has been influenced and developed over the centuries. Many other Bible reference tools are based upon the KJV. Without this, these other tools will be of little benefit.

Bible Translations: Do not rely on one translation of the Bible alone. Using just one may mislead you into hasty conclusions that cannot be defended. More than one version will train you to think critically as well as becoming familiar with what your readers are using. An accurate translation is needful for serious Bible study. The New King James Version [NKJV] serves well in this regard. It maintains accuracy while expressing the message in modern English usage.

Concordance: A concordance is a book that lists every word of the Bible in alphabetical order. Each word is shown as it is used in each verse of the Bible where it is found, beginning from the first time the word is used, and listed by the order of the books of the Bible. The most useful and comprehensive concordance for serious Bible study is Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible by James Strong. It is based upon the KJV text.

By it you can find the location to a passage that you have forgotten the reference to by remembering just one word from that verse. You can also comprehensively study every reference to a particular word throughout the entire Bible. When looking at every use of a particular word, you must also include other forms of that same word in your research. Example: an inquiry on “love” must also include “loved,” “lovedst,” “love’s,” “loves,” “lovest,” “loveth,” “loving,” “lovingkindness,” and “lovingkindnesses.”

Dictionary: A dictionary will list the proper and accepted definitions of words in English. A good dictionary will distinguish between words that are slang, colloquialisms, or obsolete in usage. The more comprehensive your dictionary is, the wider application you will gain for the usage of various terms. Do not write words whose definitions you are unsure of. Popular usage in the culture may not inform you of that.

One popular misuse in Nigeria is with the word “visible.” It is often used to express the idea of “possible or likely.” That is not its meaning. Visible means “able to be seen; to become apparent.” The misuse arose from a combination of two other words: viable and feasible. Viable means “capable of growing or developing.” Feasible means “capable of being done or effected; practicable.” The two words were mistakenly merged, both in spelling and in meaning, and it passed into common usage. In casual conversation this might be acceptable, but not in writing that may travel transculturally.

Thesaurus: A thesaurus is a treasury, not of definitions of words, but of their synonyms and antonyms. Use of a thesaurus in your writing maintains interest by substituting carefully selected terms that minimize repetition. Avoid over use of unusual words. Eliminate novel terms that may be accurate but not in the general vocabulary range of your readers. Example: “perspicacity” is generally better as “keen perception.” If you do introduce an unusual, foreign, or technical term, provide its definition at the point you introduce it into the text.

Bible Handbook: This book provides an overall survey of the contents, authorship, background, geography, history, and practices in the various biblical settings. Some useful interpretive explanations can also be found. The New Unger’s Bible Handbook by Merrill Unger is very good. Also Halley’s Bible Handbook by H.H. Halley is useful.

Vine’s: Vine’s Expository Dictionary of Old and New Testament Words by W.E. Vine is an excellent source for in-depth meanings, especially of NT Greek words for the English reader. This will prove to be of inestimable value in accurately understanding the message of the NT Scriptures. The entries are based upon the rendering in the KJV. It cannot be recommended more highly.

Bible Dictionary: This tool has numerous articles on a wide spectrum of biblical topics that expound on these subjects bringing in analysis of language, customs, cross-references, history, and at times, evaluations of other’s perspectives as well. Unger’s Bible Dictionary by Merrill Unger is a sound Bible-believing volume.

Laptop: For 1,000’s of years, all writing was done by hand: some on clay tablets, others on papyrus or vellum. Paper and ball-point pens are very recent developments in the historical flow of writing; rejoice that you have them.

John Bunyan wrote his enduring classic, Pilgrim’s Progress, with a quill feather pen while imprisoned in Bedford, England, during the early 1600’s. And that book, other than the Bible itself, has been printed, translated, and read more than any other worldwide. So don’t despair if you do not own a laptop. Just keep writing.

A laptop is an obedient electronic office assistant that does whatever you command it without mistakes or hesitation. All directives are recorded instantly in the style of letters you prefer: their size, boldness, or as italic, underlined, or capitals. What you write can be rearranged, edited, copied, added to, or deleted. And when you are through for the moment, all is preserved and neatly filed for access the next time you call upon it. Its only fee for services is occasional electricity to keep his battery full and happy.

And if you don’t know how to type, your laptop has his own assistants at his command. On the internet, go to Google Play Store and search under “typing tutor.” There you can find an App to come to your aid.

Excellent writing does not depend on excellent gadgets, but on excellent ideas and expression. Focus on those by whatever means they are preserved.

Interpretation

Biblical truth must be rightly understood in order to expound upon it accurately. The following will provide a simple guide to interpret the Word of God.

[1] Context. Words have meaning in context. The surrounding verses, the frame of reference of the biblical author, and even the context of the Scriptures as a whole provide the needed setting to understand individual verses.

[2] Harmony. All truth is one and individual truths do not contravene one another. It is needful to consider all pertinent references to resolve seeming conflicts between passages. The clear passages interpret the unclear, and asking the simple question, “In what sense?” often will help to clarify. A faulty premise will inevitably result in a faulty conclusion.

[3] Precept. The clearly stated commands and teachings in the Bible provide the basis upon which to evaluate biblical narrative.

[4] Illustration. The narratives of the Scriptures may contain spiritual illustration contained in their historical stories. These provide a vast wealth of illustrations of clearly taught biblical truth.

[5] Covenant. There is a vital distinction between the Old Covenant under Moses and the New Covenant in union with Christ. The basic difference is that what the Old demanded, it did not supply. What the New requires, God supplies through Christ. What is true of the Old Covenant externally and physically, is seen to be true in the New Covenant internally and spiritually. Christ is the end of law for righteousness to everyone who believes.

[6] Decisions. Decisions on matters not specifically addressed in the Word of God need to be determined in the following sequence: a. Direct Statements in the Bible. b. Principle. c. Examples of Christ and the Godly. d. Analogy.

[7] Study. Bible study can be approached on several levels: reading the whole Word, individual books of the Bible, topical studies, biography, and word studies.

For a full treatment of Interpreting the Bible, see the publication, Truth Rightly Divided: A Simple Guide to Interpret the Bible by Israel Jimoh and Steve Phillips. Available through Behold Print Ventures, +234 805 450 5578.

Observation

Observe carefully God’s world and the people in it. Jesus did both. Trees, fields, lightning, seeds, birds, flowers, sun, clouds, rain, night, farms, sheep, goats, serpents, foxes, thorns, vines, fruit, rivers, seas, plants, light, fish, leaven, hen, darkness, floods, dogs, wind, storms, grain, weeds, rocks, pearl, mountains, fire, water: all were suitable vehicles of eternal truth.

View God’s world through metaphorical eyes. Draw parables from life. The heavens declare the glory of God and the earth shows forth His handiwork: What are they teaching you? Grand truths are encapsulated in the everyday. Go to the ant; the stork knows her season; the garment of salvation, etc.

Illustrations from life must maintain consistent parallels derived from careful understanding of the literal before making application to the spiritual realm. Otherwise, a faulty comparison will be made. Do not take even the simplest comparisons for granted. Thorough understanding of the literal first cannot be overemphasized.

Know people and observe them well: their mannerisms, posture, vocabulary, values, aspirations, agendas, sincerity as well as deception, strengths and weakness, diligence and laziness, tenderness, callousness, what makes them weep or laugh, their motives, frustrations, integrity or compromises, flattery or honesty, love and hatred, self-restraint and outbursts, greed or contentment, self-denial or indulgence, sorrows and joys, purity or corruption. If you observe deeply, you will be able to also speak deeply.

Jesus knew all men, what was in man, and had no need of anyone to tell Him [Jn.2:24,25]. He can share that with you, for He knows; but you must study the Word very well and observe keenly if you will see men with the eye of Christ. Such insight does not come cheaply.

Insight into the times with knowledge of what the people of God should do is an on-going desperate need in Christian writing [1 Chron.12:32]. Keen perception of human character and of what God says about it will provide significant lasting value to your writing.

General Principles

Writing is condensed disciplined thought

Converting recorded oral presentation to written format does not constitute legitimate writing. Thereby the too often hasty, bland, needlessly repetitive, and inaccuracies of the tongue are preserved. Putting a thirty minute speech onto paper is quite different than spending some hours or even years to memorably inscribe multiplied reflections into clear, condensed, and disciplined written expression.

We are a generation that possesses information without wisdom and answers without solutions by gaining knowledge without reflection; Do not foster that. Give your readers substance and require them to reason with you. Lead them to see the moral and spiritual values and implications of what you are presenting and why they are so.

All worthwhile writing must bear in mind these two questions:

[1] Why am I writing this? Answering, “Because the Spirit of God has inspired me to write this book,” may sound compelling but it is not. You may simply be thinking more highly of yourself than you ought to think [Rom.12:3]. Do you truly have something worthwhile to say that the world must certainly hear?

[2] To whom am I writing? Answering, “Everybody!” may sound compelling but it is not. You cannot equally address children and university graduates in the same treatise. You cannot properly speak to Muslims and traditional worshippers at the same time. Denominational leaders and fresh converts from among youth will require different emphases and approaches. Select your intended readership carefully and consciously stick to it.

Matters of vocabulary, style, illustration, and length will be largely determined by your subject, intended readership, and constraining purpose.

Your reader is not an infant, but neither does he know what you do. Never assume that what you think about a term or topic is the same as that of your reader. If it is, you do not need to write. Your task is to enlighten, clarify, correct, impart, and expand upon what is heretofore only partially known or even unknown to your reader. Do that subtly, gently, but decidedly.

Leave no ambiguities, but do not treat the reader as an ignoramus. Lift him up graciously. Deal gently with the ignorant and misguided, help the weak, and encourage the fainthearted. Rebuke, admonish, reprove, and silence the rebellious and willfully wayward. A Pharisee and a fisherman require different tact.

Content

CONTENT, CONTENT, CONTENT. Ideas are central. Details are to augment, not to distract: too few result in confusion and too many obscure the point.

Improving your thoughts by reflecting on things of substance will translate into better writing. Deepening your meditation will deepen your written results. Reading the Word of God is paramount. Excellent authors also read widely, but don’t waste their time, energy, or abilities on the mediocre. Read the best. Study why a particular author or writing is captivating, compelling, invigorating, and delightful. Such discovered characteristics are worthy of imitation. Let them influence you.

The majority of the document should be in your own words and contain your own ideas rather than merely quoting a number of Scripture passages or citing other works. Outstanding writing should exhibit freshness both of concept and expression.

“The Scriptures testify of Me” –Jn.5:39. Let the fragrance of Christ waft heavenward from your writing. You do not need to awkwardly sprinkle the Name of Jesus periodically into your text to achieve this. But His greatness, His ways, the blessedness of His redemption, truth, holiness, and love should shine through your writing.

Fight error with truth, hatred with love, and corruption with purity. Controversies are not resolved by exchanging blows, slinging mud, or throwing stones. Christ is ever our peerless example.

It is not always necessary to quote the entire biblical verse in your writing as long as you are not omitting phrasing that does not support your citation. If you do that, you are quoting the Bible like the devil. Put down your pen; no one needs to read your thoughts.

Intent

Information is not the end of Christian writing. Messages are to be for a moral and spiritual purpose. Your writing should lead the reader to actually reorient both his thoughts and conduct. The distracting, debilitating, and destructive is to be abandoned, and the light and life you present is to be received and followed.

Excellent writing identifies and resolves a problem. Merely discussing diverse viewpoints will not be of particular help to your reader. More likely it will prove to be frustrating and lead to a sense of hopelessness and helplessness. Provide solutions, not additional confusion. Identifying a sensible and godly course of action based upon a resolution to the difficulty will be useful to the reader. Lacking that, you are simply stirring up the dust.

Confidence

A book fears no face

Do not write what you cannot defend. Avoid disclaimers. If you cannot state it boldly without apology, it probably does not need to be said. Out of reluctance to displease any, we offend all. Tempering truncates convictions. After trimming back your original assertion, the reader will think that you don’t really mean what you said and will dismiss both it and you altogether.

God does not make suggestions pending our approval. He rather speaks directly and commandingly. Do not write: “Let me make this suggestion to you…” or “I’m challenging you today…” That is providing a polite option of rejection without consequences to a non-compliant reader. If what you are saying is actually non-optional truth from God, do not weakly make excuses for it. “These things speak and exhort and reprove/rebuke with all authority/command. Let no one disregard/dismiss/despise you” –Tit.2:15.

Do not reference Greek words unless you are absolutely certain of the accuracy of your sources. Otherwise, you discredit yourself. Stating, “The Greek says…” adds no weight to your writing. It may actually detract from it. Let your insightful ideas supply weight, not borrowing from seemingly weighty sources.

Never, yes, never write, “Biblical scholars say…’ or “Historians agree…” or “the NT church believed…” For every scholar on the left, you can find an equal number on the right. And since when have historians agreed? And the NT itself is full of disagreements, departures, and errors that the epistles had to address. Let your words themselves be convincing, not by appealing to an imaginary group of intellectual or majority supporters.

If you have not yet once read the entire Bible, you are not ready to publish anything about God’s message. How would you even know if what is yet unknown to you from the Bible will agree with what you think you know? You won’t. Christian writing is to illuminate, not to spread ignorance further abroad.

Identity

Humility is the fount of all virtue. Maintain it. “For who makes you differ from another? And what do you have that you did not receive? And if you did indeed receive it, why do you boast as if you had not received it?” –I Cor.4:7. These are 3 significant questions always to be borne in mind.

“Let another praise you, and not your own lips” –Prov.27:2. Let others judge the merits of your composition, both with respect to content and expression. If your ideas are commendable and insightful but your manner of expression is poor, you are not yet ready to publish. If your grammar, structure, and style are appropriate but your content is weak, bland, trite, an echo lacking insight, or worse yet, incorrect, you yet have nothing worth sharing with the world.

Remain hidden in your writer’s closet. Do not use “I, Me, My;” it cheapens your work by blatant self-promotion and smells of conceit. Avoid statements such as, “In my opinion,” or “It has been my experience.” Your writing is your opinion and experience. You do not need to remind your reader; he already knows that.

Excellent writing exposes for public scrutiny and benefit the character of the author and his carefully thought-out perspective. If you are lacking in character, do not publish; you will infect the world with your virus. If your words are merely gleaned from others, do not publish; Google can do that better than you can. If you rush ahead to publish anyway, you will be nothing more than an echo with no voice of your own and may actually do more damage than good.

Sincere empathy for the misery of the human condition should be evident in your words. Writing having tasted of such will commend your reflections and solutions to the weary and suffering. You do not need to advertise what you have encountered and endured; the reader will know you are no stranger to affliction by your very tone of expression.

Publish because you must, not because you can. Unless there is an inner compulsion to publish your deliberations for public welfare along with confirmation from unbiased critics of your manuscript, keep your thoughts penned for private preservation. Thinking that because your mother likes it or that the members of your congregation approve are no compelling reasons to publish.

If you have unusual insight, you do not need to blow your own trumpet. Your writing itself will do that. Using phrases such as, “Few people understand this…” smells of elite arrogance and is deserving of Job’s mocking rebuke: “Truly you are the people [writers] and wisdom will die with you!” –Job 12:1.

Length

As a general principle, less is more; multiplying words to no appreciable profit is pointless and wearying to the reader. Excellent writing is graded by weightiness, not by its volume.

Better to write a tract, brief essay, or pamphlet correctly with substance than a more lengthy manuscript that is full of redundancy, extraneous diversion, needless examples, or actual emptiness because you have run out of fresh ideas. Many Psalms are less than thirty lines; some less than ten. Philemon, 2&3 John, and Jude are all one short page each. Go and do thou likewise. Volume will come with time and experience.

Style

Substance with clarity is your best style

Seek expressions that are vivid rather than bland, contain motion instead of being static, and evoke imagery in the place of the commonplace. Let the reader see, hear, taste, smell, and feel your descriptions by engaging their imagination. Example: Weak: “blue sky.” Strong: “azure heaven.” Weak: “The stream swiftly flowed in its bed.” Strong: “The renegade waters erupted with a chuckling frenzy of splashing laughter as they heedlessly dashed themselves with reckless abandon upon the unyielding stones.”

Better to be specific than general, clear rather than vague, and concrete instead of abstract. Write particulars with graphic detail using verbal pictures and images. Capture the reader’s imagination and draw him into your world to view life through your lens. The use of strong nouns and verbs does this. Example: Weak: “The sky became dark.” Strong: “The heavens grew ominous.” Weak: “Life is difficult.” Strong: “Existence weighs with hardships.”

Utilize personification of the brutish and/or inanimate: Example: Strong: “The dawn greeted the awakening meadow with her warm embrace” is more memorable and delightful than Weak: “The sun rose over the land.”

Extended Metaphor: A consistency of theme is maintained for more than one sentence to vividly impress a point. Example: [underlined words show thematic element] “The wicked slays the righteous; how oft’ this bitter bell has pealed its horrific note from the killing fields of Cain. The crescendo of this doleful symphony sounded its cacophony from Golgotha’s amphitheatre to the assembled attendees huddled around the Christ of God. Orchestrated by Satan, he conducted Caiaphas’ screeching Sanhedrin strings in concert with the pounding percussion and blaring brass of Rome’s militia to sound the death knell for the Son of God.”

Sentences and paragraphs should generally be brief yet fluid while avoiding choppiness. Lengthy sentences with numerous commas, semi-colons, hyphens, or parentheses will lose the reader; break them into two or even three. In our contemporary setting, sentences should not regularly exceed 22 words or paragraphs more than 3 to 4 sentences.

Vary sentence length. A long succession of brief sentences without interruption jolts the reader; several lengthy ones, one after the other, soon exhaust the memory.

The shorter the sentence, the greater are its demands for content. Its thoughts become compressed, approaching that of a proverb. Example: “Truth never fears error; error always fears the truth.”

Avoid the use of superlatives and exclusives unless you can defend those without controversy. Example: Acceptable: “The greatest of these is love” –I Cor.13:13. “The flesh sets its desire against the Spirit, and the Spirit against the flesh” –Gal.5:17. Unacceptable: “The worst thing in the world is death.” “Women are always more emotional than men.”

Use acronyms only after spelling out their full names unless generally known such as: USA or NT. Others should be written out first. Example: African Traditional Religion [ATR]. Independent National Electoral Commission [INEC]. After doing so, the abbreviations may be used alone.

Be cautious in the use of “always, every, no one, never, everyone;” rarely can their use be justified. Example: Acceptable: “Without controversy, great is the mystery of godliness” –I Tim.3:16. Unacceptable: “Without fail, he disappoints every time.”

Do not address your reader in ALL CAPS. This is equivalent to shouting at your reader. Unless this is called for and intentional, avoid doing so. Use exclamation marks sparingly!!! Using them often will make your reader think you are either frantic or simply eccentric. Let your words add force and emphasis, not your editorial insertions.

Redundancy discourages the reader from continuing. He will begin to feel that you have nothing further to say that will be worthwhile and will soon tire of your repetition. Better to state your points clearly and concisely once than to repeat them three or four times with no appreciable further light shed.

Unless you are refuting specific errors as in an apologetic genre, you do not need to inform the reader of four errors you are aware of before presenting the truth. Your reader will assume you know what you are talking about until you prove to him otherwise. Go straight to the point. You are writing to provide solutions, not to display your breadth of knowledge. If you do not know the resolution, put down your pen until you do.

“It is a commonly known fact that…” Eject that from your writing. Matters of common consensus are not necessarily factual. Facts are not established by opinions however widely held, but by demonstrable evidence. Give us the facts; do not appeal to them.

In many churches, “Praise the Lord” and “Hallelujah” are used as a type of punctuation mark to end one aspect of a church service and introduce another. That is profanity. Eliminate those from your vocabulary and writing unless consciously and sincerely meant as they are found in the Psalms.

Avoid the use of slang and local expressions. Slang, especially among youth, may not even be intelligible within ten years of when it came into vogue. Writing by using generally accepted phrasing will insure wide application and lasting value across even national boundaries that speak the same language.

Do not be intimidated to adopt “politically correct” nonsense terminology. Nothing is requiring you to write with gender neutral or gender comprehensive pronouns. Erase “(s)he” or “he/she” from your manuscript. For more than 400 years the use of “he” has been accepted in English literature as a generic inclusive of both male and female. It has yet to be demonstrated or accepted that this use is passé.

Here in Africa, blacks are black and whites are white and nobody gets offended. Don’t be lured into the “politically correct” jargon of “sub-Saharan indigenes and their counterparts of Anglo-Saxon descent.” That is awkward, unnecessary, and just plain silly. Your reader will wonder why the artificial pretense. The Bible deals with reality: “I am black but lovely” –S. of S.1:5. Simple; just leave it like that.

“Interesting” is an uninteresting colorless term that is regularly ambiguous at best and often void of content altogether. Erase it from your writing. If students were “interested,” tell us instead that they listened intently. If someone says the book was “interesting,” it may just be a polite way to indicate disagreement with its contents.

The same goes for “meaningful.” It is a meaningless term. Replace it with something definite and concrete. Likewise “nice;” what does that even mean, anyway? Just tell us.

Descriptive writing will revolve around satisfying the “who, what, when, where, why, and how” questions. The purpose of these are to provide a context for your reader, to eliminate confusion, while inviting him into your setting as a welcomed informed guest.

Keep descriptive phrases close to what they are modifying else confusion results. Example: “Abu took a bike back from the market from where he bought some cloth for his wife costing 50 Naira.” What cost 50 Naira, the bike transport or his wife’s cloth? Surely it was the bike ride. Rearrange to clarify.

In writing dialogue, each change of speaker will signal a new paragraph. Do not use “he said/replied” unless it is demanded in context to identify the speaker. Rely on strong nouns and verbs to indicate mood, tone, and emotion rather than adverbs editorially supplied. Example: Weak: “‘I think I can,’ she replied boldly.” Strong: “I am absolutely confident I can do that.”

Employ varied sentence structure utilizing clauses, interrogatives, exclamations, and modifying the order of subject, adjectives, adverbs, and verbs. Example: Weak: – “The man awoke in the morning and was startled.” Strong – “In the morning, the startled man awoke” or “Startled, in the morning the man awoke” or “Awakened in the morning, the man was startled.”

The place of a writer’s emphasis in a sentence is either at the end or at its beginning. Do not bury your emphatic subject or action midstream; it will be lost there.

Your first sentence should contain the seed thought of what is to follow and arrest your reader to continue. Example: in an article on worldliness: “Lot is the high-priest of a Christianity gone mad.” Once their attention is grabbed, do not disappoint them; maintain a compelling interest level throughout the remainder.

Anticipate the questions, reactions, and objections of your reader and reply to them as they naturally occur in the context of reading your manuscript. Do not defer such answers until later without providing at least a simple response at the moment. Some matters requiring more detailed explanation that would interrupt the flow of thought, can be placed in an appendix at the end of the manuscript.

The concluding sentence of a paragraph should provide a transition to the next that is a blended flow of one thought group to that of the following. Even a single word can suffice to accomplish this.

The most powerful illustrations are scriptural narratives that illumine precept, doctrine, and principle – use them. It is what God designed narrative for. Narratives illustrate doctrine, not originate it. Derive doctrine from clear declarations; illustrate with narrative.

Format

Inconsistent format invites your reader to enter your house and make himself comfortable while sitting on your sofa scattered with dirty laundry. Embarrassing disregard of format will make your writing smell because of your unsanitary carelessness.

Font

Decide on your font format and use it consistently throughout. Otherwise, you will confuse your reader. He may think you are introducing something altogether different or he may realize you are just careless. Either way, that is not your intended impression.

Your adopted font style should be clean, clear, and pleasant to read; otherwise you weary your reader.

Suggested Serif Fonts: Sitka Text [used throughout the hardcopy book] Times New Roman, Goudy Old Style

Suggested Sans Serif Fonts: Ariel , Calibri

You may use more than one font style in your document; just be purposeful and consistent. It may be helpful to make yourself a reminder note for reference as you write. Example:

Text Font: Times New Roman 11point.

Chapter Titles: Felix Titling font, bold 16point

Sub Headings: Felix Titling font, italics 14point.

Emphasis: Times New Roman font, bold 11point.

Bible Quotations

Use one form to indicate quotations of Bible passages. Any of the following examples are acceptable:

“For God so loved…” For God so loved… For God so loved…

Do not combine these; it is unnecessary and tortuous to the eye. Example of what not to do: “For God so loved…”

Citation of references to Bible quotations should be consistent. You can choose to write out the entire name of the Bible book. If you do, do it throughout.

Abbreviations as shown below can be used in standard format. Do not invent your own abbreviation scheme or your reader will be confused. Many Bibles will show abbreviations at the beginning. Standard abbreviations can be gleaned from references provided within the text of your Bible.

Example: Ezekiel is Ezek. John is Jn. Deuteronomy is Deut. Wrong: Ezekiel is Ez. or Ezl. John is Jo. Shorter names of books may need no abbreviation such as Job or Jude or Joel.

Example: of acceptable referencing formats:

“For God so loved” –Jn.3:16.

For God so loved [Jn.3:16].

For God so loved (Jn.3:16).

Note: [1] Punctuation comes at the end of the reference notation, not after the words of the quote. Otherwise the reference is left hanging as if it were a separate sentence. [2] Reference notations should not be bold or italics; they are not part of the quotation but merely inform where the verse can be located.

General

Typically, do not spell out numerals. Example: “25-10-2019. Chapter 2. 1,000 yams.” If the numerals occur in dialogue, then they are spelled out. Example: “I am reading chapter ten now.” “I just had my twenty-first birthday.”

When mentioning the titles of books within your sentence, they should be italicized. Example: “The brief book It is Written! gives suggestions to improve writing skills.”

Decide whether you want to indent paragraphs or whether you will double space between them to indicate paragraph breaks. This book has double spaces between paragraphs for cleanness and clarity in locating content easily since it is somewhat of a reference book. Other books have indented paragraphs. You decide, but don’t do both. If you are trying to save space and number of final pages, indent.

Use full justification of your text as shown in this book. If you justify left, your right-hand margin will look ragged and inconsistent.

Procedure

Write your Big Idea in one sentence

Write, write, and then write some more: seed thoughts, inspirational ideas/themes, and arresting expressions. They need not be lengthy: something simple to trigger development later. Don’t worry about polished final form as you do; that will come with revision and time. Jot down your reflections regularly for future meditation and expansion. Write these in a ledger or as suggested in the following.

Maintain two accordion files – one alphabetic, one by books of Bible. The alphabetic file will contain seed thoughts, inspirational phrases that come to mind, topical data, themes, and articles. The biblical file will be for filing notes on specific verses, chapters, and books of the Bible. These will become your resources for present and future projects.

When you have settled on a topic, follow this procedure.

WHAT IS YOUR BIG IDEA? State it in one sentence.

This determines all that follows.

Answer these questions and you will have your OUTLINE:

[1] INTRODUCTION: What does the reader need to know to provide a context for my Big Idea? [Background, definitions, comparisons, contrasts]

[2] BODY: What content and illustrations are needed to express my Big Idea? [Major points, references, examples, citations, supporting evidence, applications, transitions]

[3] CONCLUSION: How can I summarize my Big Idea so the reader will understand it as I do? [Highlight the theme, contributing concepts, and final significance]

Tell them what you want to say [Introduction], say it [Body], and tell them what you have said [Conclusion]: but absolutely avoid an obvious and mechanized approach of doing so.

There are three necessary phases of quality writing

[1] Content. This, for the Christian, is the most critical aspect of writing. We desire to convey truth that is consistent with the Word of God so as to represent Christ as He is presented in the Scriptures. At this stage, final form is not your concern: capturing concepts and truth is. Do not be concerned at the outset of whether your thoughts are complete and properly recorded on paper; just jot them down, even if incomplete. Diligently examine your ideas at this stage and arrange them in order according to the overall purpose of your Big Idea.

Content is derived from careful reflection on the biblical text as well as understanding the condition of man. Much content is obtained through protracted study, data gathering and analysis, and recording your findings. Some ideas may come like a flood into the mind. Write all of these down. They will serve as your resources for expressing your Big Idea.

If you are struggling over a particular chapter or section, set it aside. Go onto something else that flows as you write. Come back to the difficult portion later. When you do, you may be more refreshed and determined as you write that section. It is not necessary to write in rigid sequence. At the Content stage, just get your key ideas and inspirational expressions down on paper.

In the writing of a particular book, the last chapter was the very first one written. The author knew where he wanted to land, and everything moved towards that goal. Another book was written nearly entirely out of its final sequence: a portion of chapter 3 here, something from what became chapter 6 there, etc. Once the ideas are captured on paper or laptop, it is easy to rearrange them from there.

Whenever you sit down to write, write something, even if it is brief. This develops the discipline of putting your ideas into a durable form. It will provide a basis for development later. When an idea comes to mind during the activities of the day, commit it to writing, even if on a scrap of paper. It will remind you later when you have the opportunity to add it to your manuscript or file for the future.

[2] Expression. Second, you must now put your ideas into clear and proper expression. Your objective at this stage is to adjust the way in which your ideas are being expressed. You must rigorously bear this in mind as you revise and re-write; what will the reader understand by the way in which I am expressing myself?

Attention here is given to appropriate vocabulary, sentence length, spelling, grammar, and flow of thought. Always you must bear in mind at this stage: Who am I writing for? Are they well educated or not so much; old or young; Christian or not?

Write as if you are preserving something of enduring value for succeeding generations. Write with a consciousness of the great cloud of witnesses surrounding you [Heb.12:1]. Will Moses, David, Isaiah, John, Paul, and Peter rejoice in what you are writing? “Your testimonies are my delight; they are the men of my counsel” –Ps.119:24. In other words, let your writing contribute to the on-going valuable explanation of God’s unchanging truth.

[3] Editing. Finally, attention must be given to matters of form, font, indentation, punctuation, verb agreement, and consistency of using bold, italics, sub-headings, etc. Here, you are reading through the manuscript once again, this time as an editor looking specifically for these details.

Your reading at this stage is not as an author to analyze content and expression; that has already been done. Editing is the final step after matters of content and expression have been settled. If your writing will have enduring value, much care is needed at this juncture.

Become your own worst critic. Do not flatter yourself imagining that because your words are on paper, that they are fixed and final or even worthwhile. Never be content with the mediocre; relentlessly revise, delete, and rewrite. Only the Word of God is inspired and forever settled in heaven; your own writing is not.

Consistency is paramount in spelling, punctuation, grammar, fonts, capitalization, quotations, parentheses, formatting, subtitles, indentations, and spacing. Tirelessly correct all inconsistencies thus developing disciplined diligence. Careless people will not be aware of many inconsistencies as they read, but that is not your standard.

If you wish your work to endure and be read by the widest readership, it will not be read if you are careless about your editing. Carelessness in edited form will result in your content being cast aside as unworthy. In the mind of the reader, laziness in edited details translates to laziness of the author’s thinking abilities.

Avoid the use of passives. Example: Poor: “He knew not.” Better: “He did not know.”

Insure that the antecedents of pronouns are clearly identifiable. Example: “Paul and Timothy went into the market and he said to them…” The antecedent is unclear; is it Paul or Timothy who spoke?

Take full responsibility for all that is published by your pen: all ideas, format, grammar, punctuation, and mistakes. Resist the temptation of pointing the finger like Eve and saying, “The printer did it!” You are the one responsible for final editing, not him. If the printer is actually at fault, take the blame yourself, correct the problem, or find another printer. That is the way of integrity.

The purpose of a Table of Contents in longer works such as a book, is to allow readers quick access to your principal concepts. In shorter articles and booklets it is optional. Chapter titles should indicate generally where those concepts can be located in your document. Chapter titles that are vague or misleading will not be helpful to your reader. The Table of Contents of this book is a suggested example.

For further on Procedure see Appendix: Grammar & Punctuation

Genre

Novel/Short Story – usually recounts the conflict between the protagonist [main character/concept or “hero”], the antagonist [main opposing person/idea or “villain”], those caught in the conflict [supporting characters/ideas], the principles upheld, virtues engaged, and wickedness employed that lead up to a crisis and final resolution. The conflict can be within the same individual as when struggling over a decision. Characters should be realistic with identifiable personality traits and not idealistically incredible.

Devotional – usually is one to two paragraphs and up to one page to encourage, uplift, exhort, or enlighten. Devotional writing, by way of contrast to Exposition and Exegesis, often takes a verse or phrase as an apt expression of a truth established elsewhere in the Scriptures and utilizes that as a header of sorts to sum up its point.

Example: “He is Able” – the sufficiency of Christ. “He does all things well” – Christ’s dependability. “It is finished!” – The fullness of our salvation. In each of these, a verse or phrase is wrenched from its context to express a theme not found within the verse itself. It is a legitimate manner of writing, though caution is advised in the same sense that narrative is to be interpreted by precept and not precept being derived and established by narrative. Just make sure you are writing legitimate truth.

Topical – involves data gathering, analysis, and synthesizing of relevant particulars. On a biblical subject, examine every pertinent verse on a given subject so as to possess a comprehensive grasp. Data gathered must then be arranged in obvious and relevant subheadings. Then the message of the verses themselves must be determined by careful reflection and comparison. Finally, a main thesis or message will emerge as a conclusion. Then with confidence one may declare, “Thus says the Lord.”

Exhortation – is persuasively provocative to alter behavior to a higher degree of devotion and godliness. It is effectively presented with its sting in the tail, i.e. with a powerfully pointed conclusion. Example: Stephen’s message in Acts 7.

Expository – is based upon a grammatical scrutiny of words, verses, and chapters in context: particularly needful in the NT epistles. Exposition is a particular genre of writing that explains and amplifies the content of a passage so as to bring out its message with clarity. It is distinguished from Exegesis which deals with linguistic elements of grammar, syntax, lexicography [definitions], and context to accurately express what is being said.

Exegesis deals with what is said, Exposition with what is meant. Obviously, all Exposition will necessarily involve Exegesis, but not all Exegesis will include Exposition. Exposition will employ background, illustration, cross-references, setting, and relevant history to enhance and explain the meaning contained in the actual words of a passage. Commentaries are an example of this.

Apologetic/Controversy – involves persuasive argumentation to demonstrate a point and silence opposition. To be effective, one must understand the opponent’s viewpoint better than he does while proving its deficiency. The problem, error, or contention must be clearly identified before systematically demonstrating its falsehood. But do not fail to provide a solution. Even imbeciles can throw stones; to build with them requires a person of skill.

Biography – Excellent biography will expose the hidden inner movements within the heart and character of the subject, not merely a recounting of his movements without in time and place. How has his character been shaped? What events and crises have been overcome and how? Describe his human relationships and the influence he has had on others. A catalogue of achievements, credentials, and recognitions fall far short of describing how he excelled in triumphing over that greatest of all challenges: Self.

Translating – from one language to another requires great patience, knowledge, and skill. Thought forms, and the sequence of nouns, verbs, and modifiers may differ from one language to another. Expressions common in one language may not even exist in another. Equivalents must be selected with care. Repeated discussion must take place between author and translator to insure accurate conveyance of concepts.

Academic – is best left in the university. For general readers, it is ponderous and too often irrelevant to their life-context. Do your research, yes, but do not express it within the rigid academic format if you wish your writing to actually be read and be a blessing to many.

Parables, poems, proverbs, riddles, allegory, screenplays, reporting, songs, and hymns are specialized and distinctive types of writing.

Experiment

Experimentation with different types of writing will develop your observation, thinking, and writing skills. They may lack brilliance at first, but they will expand your inner resources of what might eventually become brilliant.

Parable – Write an original parable; it will help translate biblical truth into life situations in your mind.

Poems – These will provide an avenue for your heart’s emotions, worship, and aspirations to have a structured outlet.

Proverbs – Original proverbs of your composition will focus your observations about life into memorable condensed expressions that capture valuable assessments.

Allegory – is an extended parable taking much skill to maintain over many pages without becoming a cheap imitation of other existing literature or filled with obvious and trite comparisons that spoil its winsomeness. Save writing allegories until you are fifty years old.

Songs – If you are not a musician, you can still write worthy songs and hymns of worship. Choose an existing delightful tune and compose new words within the existing meter of the tune. Then, at least, you have preserved your own expression of praise to Christ whether it ever obtains public recognition or not.

Appendix: Grammar & Punctuation

Grammar

Definitions: There are 8 parts of speech.

[1] Nouns are persons, places, or things [including ideas, emotions, and desires].

[2] Pronouns are words that stand in the place of nouns to avoid awkward repetition. Example: “Abu thought that Abu should go to Abu’s house” [grammatically correct, but clumsy]. “Abu thought that he should go to his house” [much smoother, clearer, and natural].

[3] Adjectives modify [describe or qualify] nouns or pronouns.

[4] Verbs are action words [including thinking, believing, feeling, sensing, etc.]. Verbs tell what is happening.

[5] Adverbs modify [describe or qualify] verbs and at times also adjectives or other adverbs.

[6] Prepositions are used before a noun or pronoun to show their relationship to other words in the sentence: words like “in, at, by, through, with, to, from, into, around, etc.” There are about 60 prepositions.

[7] Conjunctions connect words or clauses. The most common are “and, or, but, because, since, that.”

[8] Interjections are exclamations of sorrow, disbelief, excitement, alarm, anger, etc. Example: “No!” “Kai!” “Stop!” “Run!” “Hurray!”

Sentence: is a group of words arranged to express a complete thought. The minimum requirements are a subject and predicate [a word or words that make an assertion about something: a verbal idea]. Example: “Dogs bark.” “Are you going to the market?”

There are 4 kinds of sentences.

[1] Declarative makes a statement. “Abu is tired now.”

[2] Interrogative asks a question. “Where is Abu staying?”

[3] Imperative expresses a command or a request. “Tell Abu to come.” “O Lord, have mercy.”

[4] Exclamatory expresses strong feeling. “I hate everything about pride!”

Every sentence will contain at least one Independent Clause [IC] and may also have one or more Dependent Clauses [DC]. An IC contains a complete verbal idea and can stand alone as a sentence. A DC must be attached in relationship to an IC. A DC cannot stand on its own. Example: “Abu pounded yam in a new mahogany mortar.” “Abu pounded yam” is a complete verbal idea and thus can stand alone as a sentence [IC]. “in a new mahogany mortar” cannot stand alone since there is no verbal idea contained in it [DC].

Infinitive: is best not split by an adverb unless you particularly wish to emphasize the modifier. Example: “to hastily depart” is a split infinitive. It is better written as “to depart hastily.”

Common Misuse of Terms

“Which” and “that” are generally used interchangeably, but proper style would defer to using “that” as the preferred term. Use your ear as to which sounds best in context and choose that one.

Common Latin abbreviations are: etc. meaning “and others of a like kind; and the rest; and so on.” i.e. meaning “that is.” e.g. meaning “for example.” cf. meaning “refer to.” f meaning “and following.”

“Prophecy” is a noun. “Prophesy” is a verb.

“Can” means “am/is/are able.” “May” means “opportunity, possibility, permission.” Example: “I can come [am able] unless my employer may not [possibility] give me permission.”

“Effect” as a noun means “result.” As a verb it signifies “to accomplish.” “Affect” is a verb meaning “to influence.”

“Altar” is a noun: “a place/structure where sacrifice is made.” “Alter” is a verb: meaning “to change or modify.”

These two terms always go together as husband and wife; do not separate what has been joined together: “either/or” and “neither/nor.”

Write “first, second, third,” not “firstly, secondly, thirdly.”

“Its” is possessive. “It’s” means “it is.”

Subject and verb agreement: if the subject is singular, so must the verb be; if it is plural, use a plural verb.

Punctuation

Commas

Enclose parenthetic thoughts with commas before and after. Example: “Abu, the newest member of the team, was chosen to be captain.” Names and titles in direct address also are offset with commas. Example: “Excuse me, Sir, is this your pen?” Place a comma before a conjunction introducing an independent clause. Example: “Abu is not back yet, and night is coming.”

Semicolons

Two independent clauses closely related can be joined with a semicolon [ ; ] when there is a kind of cause and result relationship between them. Example: “He believed the gospel; he became a changed person.”

Colon

Two independent clauses can be joined with a colon [ : ] when the second interprets or further explains the first. Example: “He collapsed shakily on the sofa: fatigue from three days of not eating had overwhelmed him.” A colon can indicate a further explanation or an example. Example: “Abu hurriedly gathered his things: shoes, shirt, and whatever else he could grab.” It may also introduce a quotation. Example: “We heard Abu say: ‘I object to that.’”

Dash

A dash [ — ] introduces an abrupt interruption in the flow of thought to insert something in passing. Example: “The elections – if they can even be called elections – in Nigeria are over.” The dash is not regularly used; typically other punctuation marks serve this purpose such as commas or parentheses.

Hyphen

Two or more words that are combined to form a compound adjective are to be joined by a hyphen [ – ]. Example: “self-willed” or “hot-headed.” A hyphen can also divide a word between syllables at the end of a line if the entire word does not have space to contain it. Example.

Parentheses

Parentheses [ ( ) ] serve to insert an idea or explanation that will help to clarify the statement of the sentence. When they occur within a sentence, the punctuation takes place outside of the parentheses. Example: “Abu went to see him (after many attempts), but he was not yet at home.” If the parenthesis itself requires punctuation, it is placed within the marks. Example: “Abu said (and why should we doubt him?) that Chide has gone.” (If the whole sentence is a parenthetic, the final punctuation goes inside the final parenthesis mark.) Just like that. Note: parentheses are plural; parenthesis is singular.

Quotation

If quotation marks [ “ ” ] are used within a sentence, commas are placed within the quotation marks. Example: “I spoke to Abu yesterday and he said, ‘I will come Tuesday,’ so we should prepare.” At the end of a sentence, the punctuation goes inside the quotation mark. Example: Abu said, “Come!”

When there occurs a quotation within a quotation, the following form is used. “Rightly did Isaiah prophesy of you hypocrites, saying, ‘This people honors Me with their lips, but their hearts are far from Me.’” Note: if the second quote concludes at the end of the sentence, both marks must appear.

The opening quotation mark will always be written [ “ ]. A quotation within a quotation will be indicated by using the single apostrophe mark [ ‘ ].